Getting to zero

By Martha McKenzie l Photography by Bryan Meltz

|

|

|---|---|

James W. Curran | Epidemiologist

ENDING STIGMA CRITICAL TO SUCCESS

When AIDS first emerged, those infected were often seen as pariahs, both because they were believed to be highly contagious and because they came from disenfranchised groups. Thirty-five years later, the stigma still persists. It exists on the individual level, isolating those infected from families, friends, and even health care providers. It exists on the societal level, with laws, policies, and regulations that target people with HIV. Both forms result in a reluctance of individuals to get tested and/or treated, which not only adds to their suffering, but also interferes with attempts to control the disease. There is no quick fix, only patience and persistence. Ronald Valdiserri, author of Gardening in Clay: Reflections on AIDS, said fighting discrimination is similar to weeding a garden. You can’t ever let your guard down or the weeds will crop back up, but the more diligent you are, the easier the task becomes. If we do not weed out stigma and discrimination, we will not be able to end the AIDS epidemic.

James W. Curran is the James W. Curran Dean of Public Health at Rollins and co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research (CFAR). Prior to joining Rollins, he led the nation’s battle against HIV/AIDS at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

|

|

|---|---|

Carlos del Rio | Clinical Researcher

DON’T ALLOW COMPLACENCY TO ERODE GAINS

The novelty of HIV has been lost. Treatment advances that have turned HIV into a chronic condition rather than a death sentence have led to a sense of complacency. And while it’s true that we now have the tools to end the epidemic, much work remains to be done. That means we can’t allow funding for research, prevention, and treatments to wane. In the United States, where just 30% of the 1.2 million people living with HIV are treated effectively enough to suppress their virus, it’s clear we need to design better health care systems that can get patients’ viral loads to undetectable and keep them there. Even then, it’s unlikely treatment alone will be powerful enough to end the epidemic. For that reason, research toward long-acting treatments, a cure, and a vaccine must continue. We have the tools to end the AIDS epidemic. We just need the will to do it.

Carlos del Rio is Hubert Professor and chair of the Hubert Department of Global Health and professor of medicine in the Emory School of Medicine. He is co-director of CFAR at Emory and chair of the HIV Medicine Association.

|

|

|---|---|

Eric Hunter | Pathologist

CONTINUE WORKING TOWARD A VACCINE

The key to ending the HIV epidemic is a protective, affordable vaccine that prevents the virus from establishing infection. The beauty of a vaccine is that once a person has been vaccinated, the body automatically responds to protect itself against infection— it doesn’t require a conscious action on the part of the potentially exposed person. Indeed, history teaches us that a protective vaccine, as opposed to treatment alone, is the only way to eradicate a pathogen—the vaccines for polio or smallpox are great examples of this. Because HIV attacks and can lay dormant in cells of the immune system, developing a vaccine against it is one of the more difficult scientific problems of our time. Progress is being made, and what we learn will also be important for developing vaccines against other viral diseases.

Eric Hunter, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Emory School of Medicine, is co-director of CFAR at Emory. In his laboratory at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, he studies how HIV enters cells.

|

|

|---|---|

Guido Silvestri | Virologist and Physician

FIND A FUNCTIONAL CURE

A very important priority in contemporary HIV/AIDS research is the development of a “functional cure” for the infection. Indeed, despite the reduction in mortality and morbidity due to antiretroviral therapy (ART), the cost of these drugs places an inordinate burden on public health systems. While patients who have access to lifelong ART are often able to reduce their HIV viral load below detectable limits, a treatment that can eradicate or functionally cure HIV infection remains elusive. In recent years, we and others validated the pathogenic model of simian immunodeficiency virus infection of rhesus macaques for studies of HIV cure. It is likely that interventional studies in this highly relevant animal model will help assess the therapeutic potential of novel interventions aimed at reducing this virus reservoir in ART-treated, HIV-infected individuals.

Guido Silvestri, professor of pathology at Emory School of Medicine, is chief of the Division of Microbiology & Immunology at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center. Since 1993, Silvestri has been involved in studies of AIDS pathogenesis, prevention, and therapy, mostly using nonhuman primate models of SIV and SHIV infection.

|

|

|---|---|

Hannah Cooper | Social Epidemiologist

STOP TRANSMISSION AMONG PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS

People who inject drugs (PWID) were among the first hit by the AIDS epidemic in the U.S., particularly New York. In those early days, about half of all people who were injecting drugs in New York were HIV positive. Users and allies banded together to create a strong infrastructure to stop transmission—they set up syringe exchange programs, strengthened drug treatment programs, and promoted access to antiretroviral therapy—and it worked. The city has dropped to almost zero transmissions among PWID. We’re now seeing an uptick in the number of PWID, fueled by an epidemic of prescriptive opioid misuse. These PWID, however, are scattered across the country, often concentrated in rural areas. We need to adapt the strategy New York used so successfully, taking advantage of the federal government’s recent lifting of the ban on needle exchange programs and of the availability of new drugs to treat opioid addiction.

Hannah Cooper is vice chair and associate professor of the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education at Rollins and co-director of the Prevention Sciences Core for Emory’s CFAR. Her research focuses on the social determinants of drug use, drug users' health, and health disparities.

|

|

|---|---|

Igho Ofotokun | Physician and Scientist

INCLUDE TESTING IN ROUTINE MEDICAL CARE

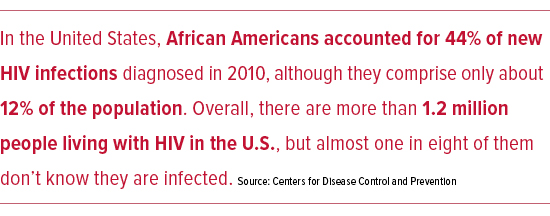

More than 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV, but almost one in eight don’t know that they have it. These undiagnosed individuals play a large role in spreading the infection, accounting for about a third of new cases in the U.S., according to the CDC. These people are also not getting the treatment they need to prevent the progression to AIDS. HIV testing should be rapidly scaled up and incorporated into routine medical care, including annual physicals and perhaps even dental checkups. High-risk individuals should be screened annually. Linkage to care for newly diagnosed individuals should be as seamless as possible. With currently available tools, the goal of zero new infections is attainable and should not take another three decades.

Igho Ofotokun is an associate professor of medicine at the Emory School of Medicine, a staff physician at Grady Health System, and a clinician scientist with CFAR at Emory.

|

|

|---|---|

Jessica Sales | Developmental Psychologist

EDUCATE THE NEXT GENERATION

Today’s youth are coming of age when HIV and AIDS are no longer making headlines, so it’s easy for them to think of AIDS as a problem of their parents’ generation. That’s why education, especially among youth (ages 13-24 years) is a key factor to ending the HIV epidemic. Surveys consistently indicate that U.S. parents overwhelmingly support comprehensive, medically accurate, age-appropriate sex education in schools, but it is all too often not provided. Schools should offer unbiased, LBGT-inclusive curricula that provide students with necessary information and skills to prepare them for responsible decision-making and protecting their sexual health over the course of their lives. School-based sex education should start early and continue throughout students’ school careers. Yet courses cannot and should not supplant discussions at home about sex, which also protect the sexual health of youth. In addition, health care providers can offer a vital safety net for valid, reliable sexual health education by allotting time alone for confidential consultation as part of every adolescent health care visit.

Jessica Sales is an associate professor in behavioral sciences and health education at Rollins. She is an investigator in the Emory CFAR, as well as a research scientist in the Center for Translational and Prevention Science.

|

|

|---|---|

Natalie D. Crawford | Social Epidemiologist

END RACIAL DISPARITIES

Racial and ethnic disparities are persistent across every facet of HIV—from transmission to diagnosis to treatment. Specifically, black and Latino Americans compared with white Americans have a higher incidence of HIV, are diagnosed at a later stage of disease, and are less likely to receive and achieve successful treatment. Research has consistently shown that racial and ethnic minorities engage in fewer sexual and drug-using risk behaviors that would put them at risk for HIV compared with whites. So, it’s clear that social determinants operating on individual and institutional levels are creating differential risk for minorities through higher-risk social networks, lower health care access, higher policing, and poorer neighborhood environments. We cannot get to zero in HIV without concerted public health research and practice that change or circumvent these very salient structural systems that are unique to racial and ethnic minorities.

Natalie D. Crawford is assistant professor in behavioral sciences and health education at Rollins. Her research aims to inform interventions and policies designed to reduce substance abuse and high-risk sexual behaviors.

|

|

|---|---|

Patrick Sullivan | Epidemiologist

RAISE AWARENESS AND USE OF PrEP

A daily pill that can provide powerful protection against HIV has been available since 2012, yet few take advantage of it. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) reduces the likelihood of contracting the virus among HIV-negative individuals who engage in high-risk behaviors by as much as 90%, yet currently less than 3% of men who have sex with men have ever taken it. Why? Many of the people who need it most don’t know about it. At Emory, we’re thinking about new ways to use mobile apps to provide high-risk gay men with information about PrEP, to help them decide whether PrEP might be right for them, and to help them find a provider near them who can prescribe PrEP. To increase uptake of PrEP, it will be critical to take advantage of new technologies.

Patrick Sullivan, professor of epidemiology at Rollins, has 21 years of experience in HIV epidemiology, prevention, and behavioral surveillance. He developed AIDSVu, a compilation of online maps that show the most recent HIV prevalence data at national, state, and local levels.

|

|

|---|---|

Raymond F. Schinazi | Virologist and Chemist

FIND HIV’S HIDING PLACE

The most critical question in the HIV cure agenda is finding where the virus is hiding. With hepatitis C, the target is in the liver. With various types of cancer, we know the organs affected. But with HIV, we just don’t know where it’s hiding. People have theories—it’s in the T-cells or it’s in macrophages in the lungs or brain. We are working to develop a method to light up an area in which the virus is residing. Then we could target that specific area and direct all of our considerable firepower toward that. Otherwise it’s like target shooting when you don’t know where the target is.

Raymond F. Schinazi is the Frances Winship Walters Professor of Pediatrics and Director of the Laboratory of Biochemical Pharmacology at the Emory School of Medicine. He serves as director of the Scientific Working Group on HIV Cure within the CFAR at Emory. With Dennis Liotta and Woo-Baeg Choi, Schinazi developed Emtriva, an antiretroviral drug taken by more than 90% of people who have HIV in the U.S.

|

|

|---|---|

Susan Allen | Prevention Researcher

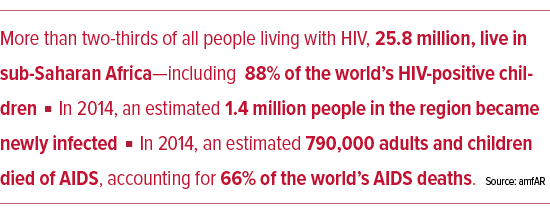

TEST AND COUNSEL COUPLES IN AFRICA

Most HIV infections worldwide are sexually transmitted. In the vast majority of transmissions, the two partners do not know that they have a different HIV status. In Africa, where more than two-thirds of HIV-infected people live, most existing and new HIV infections occur among married men and women who do not know it is possible for couples to have different results. Testing couples together with joint disclosure and counseling and providing condoms reduces risk of HIV by more than two-thirds without antiretrovirals and is low cost, sustainable, and recommended by the World Health Organization. Joint counseling also reduces the risk of other sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancies. Unfortunately, because of the pharmaceutically focused HIV agenda in Africa, fewer than 5% of couples have been tested and counseled together. Rwanda has succeeded in nationalizing this program, providing funding agencies with an opportunity to replicate this success.

Susan Allen is professor of pathology and laboratory medicine in the Emory School of Medicine and founder of the Rwanda-Zambia HIV Research Group (RZHRG). Since 1986, RZHRG has studied HIV and unplanned pregnancy prevention and correlates of transmission from man to woman and woman to man.

|

|

|---|---|

Wendy Armstrong | HIV Clinician and Clinical Researcher

INCREASE THE PERCENTAGE OF HIV-POSITIVE PEOPLE ON ANTIRETROVIRALS

At first glance, achieving this goal seems to hinge on diagnosing all those who are infected—find them so you can treat them. In reality, the challenge is in linking the diagnosed to care and retaining those patients in care over the long term. Retention is hard, in large part because social determinants of disease are important cofactors for those most affected by the epidemic in the current era. Our systems are designed to best help patients after they walk into the clinic. We need to recreate our care delivery systems to better meet patients where they are. We must enhance outreach, help with transportation, combat stigma, promote personal relationships within the health care system, and provide coordinated medical, mental health, and substance abuse care. These are the interventions that will help increase the percentage of patients on long-term ART.

Wendy Armstrong is a professor of medicine at Emory and medical director of the Infectious Disease Program at Grady Health Systems. She is the chair-elect of the HIV Medicine Association.