Cultural exchange

By Martha McKenzie | Illustration by Sam Falconer

Hubert H. Humphrey Fellowship Program celebrated its silver anniversary at Rollins and its 40th anniversary as a program. Former President Jimmy Carter started the fellowship as a way to honor the late senator and vice president who had dedicated his career to the advocacy of human rights and international cooperation. The program brings accomplished mid-career professionals from designated developing countries to the United States for one year of non-degree graduate study and practical professional experience.

Rollins hosted its first cohort of 11 fellows 25 years ago under the leadership of Dr. Philip Brachman, former professor of global health and epidemiology. Brachman continued to run the program—enthusiastically and devotedly—until his death in 2016. Dr. Roger Rochat, professor of global health, succeeded him. To date, Rollins has hosted 222 fellows from 96 countries.

For the fellows, the year at Rollins is often transformative. In addition to academic work, fellows participate in workshops, conferences, and professional affiliations that provide interaction with leaders from all levels of government, multinational organizations, and the private sector. And they join a network of Humphrey Fellows.

“The African Humphrey alumni have just set up a listserv to stay in touch with each other,” says Rochat. “The 20 Humphry alumni in Myanmar meet once a month. The connections they make here are leading to new initiatives, which is phenomenal.”

For Rollins and Emory, the fellows offer a rich resource of diverse views and experiences. Dr. Jennifer Sarrett invites fellows to give guest lectures in her undergraduate Health and Human Rights course. “While I can teach the students about issues related to health and human rights around the globe, nothing I can do can match the experience of learning about issues from those on the ground, working directly in these areas,” says Sarrett.

As he does every year, President Carter addressed the most recent class. He reflected on establishing the fellowship 40 years ago and the impact Humphrey fellows have had—and continue to have—on the United States and their home communities around the world.

Here’s a small sampling of some of that impact.

Invaluable networking

The most valuable thing Sangay Phuntsho took away from his 2015-2016 Humphrey Fellowship was connections—both fellow classmates and professionals at Rollins, the CDC, and elsewhere. A senior program officer with the Department of Public Health, Ministry of Health in Bhutan, Phuntsho had never studied in a developed country before he came to Rollins, so his knowledge and professional network were limited and local.

“The fellowship has changed my way of working,” says Phuntsho. “We are a small and a developing nation, so we really need to enhance progress at an unprecedented rate and keep up to date with the world. Seeing the health care system of a developed country was eye-opening. The contacts that I made while I was there are proving very beneficial.”

Charged with managing the national immunization program in Bhutan, Phuntsho took advantage of every opportunity to learn more in this area. He worked with experts at the global immunization division of the CDC and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), attended a global polio eradication training program, took classes on infectious diseases and cost-effectiveness of health programs at Rollins, and attended many more workshops and seminars.

When he returned home, he discovered he needed help doing a rotavirus vaccine cost-effectiveness study in line with the country’s new vaccines introduction plan. He reached out to one of the vaccine experts he met during his fellowship and got the assistance he needed. He hopes that Bhutan can introduce rotavirus vaccine to the routine immunization program in the near future.

The fellowship, however, was not a one-way street. Phuntsho felt he had much to offer to his fellow classmates and did so through several presentations. “I was an ambassador for my country,” he says. “We are very small, but in our own small ways, we are rich in our culture, tradition, and environmental preservation. I come from a country where the progress of the nation is being measured in terms of the happiness level of its people, unlike the gross domestic products in most countries. It’s a very different development paradigm that I am proud to share.”

A social justice perspective

Carol Palmer came to her Humphrey Fellowship in 1999-2000 with an extensive background in health, having served as a physical therapist, Jamaica’s resource person on quality for the World Confederation of Physical Therapy, and a planner for Jamaica’s Ministry of Health. The fellowship broadened her view of health.

“We studied health and social justice, and it gave me exposure to how health impacts one’s life totally,” says Palmer. “We learned how social ills impact your health, which in turn impacts society. It heightened my sensitivity to the needs of others, and I brought that back with me and applied it to everything in my life.”

This new sensitivity played a role in her decision to switch from the Ministry of Health to the Ministry of Justice, where she drove Jamaica’s agenda for restorative justice. Thanks to those efforts, the country has begun diverting young offenders in minor crimes from the criminal justice system to a child diversion program that offers behavioral change counseling.

Palmer spearheaded Jamaica’s National Task Force Against Trafficking in Persons, which she still chairs. The task force has a three-pronged approach to curbing trafficking—rescuing victims; ensuring funding for their housing, medical needs, clothing, food, and counseling; and educating the public about human trafficking. Palmer’s efforts were rewarded with the Pinnacle Award, given by the U.S. Embassy’s Stakeholder Appreciation and Recognition Awards Committee.

Palmer has most recently moved to the Ministry of Science, Energy and Technology, where she serves as permanent secretary. “I still talk about the Humphrey fellowship all these years later,” she says. “The whole program focuses on the question, ‘How do you make your society a better place?’ I’ll do everything I can to make sure I’m making a positive contribution to change in the world.”

Protecting sight

Priya Adhisesha Reddy has spent her career trying to save the vision of people, particularly children, in poor resource settings. In addition to serving as project manager and patient care manager with Aravind Eye Care System in India, she has led countless research projects. She implemented a diabetic retinopathy project where 30,500 patients benefited from treatment and led a school screening project that screened more than a million children for vision problems.

She came to the Humphrey Fellowship in 2016-2017 with the goal of learning more about health care economics, policies, and advocacy so she could continue and expand her work. Reddy was particularly impressed with the cross-cultural learning from fellows from other countries, an internship with USAID, and courses in research writing, which she says have helped her professional development.

Upon returning to India, Reddy led a study that got broad recognition after its publication in The Lancet. The study measured the effect of providing glasses to correct presbyopia (an age-related eye condition) among tea workers aged 40 years or older. The simple intervention improved productivity by 22 percent over a three-month period.

Reddy is also working as a consultant for the Seva Foundation, a Berkeley-based nonprofit dedicated to eliminating avoidable blindness. In this role, she is evaluating a program that helps 54 eye hospitals in India develop their surgical knowledge and improve their training and capacity building. And she is pursuing her PhD in medicine at Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Trees in the desert

The Humphrey Fellowship changed Anwar Sarhan’s career trajectory. Prior to his 2006-2007 fellowship, he worked as an occupational therapist at a government public hospital in Bahrain, a position he planned to continue.

Then he spent time with professionals like Phil Brachman, “who really make a career out of helping people,” says Sarhan. “I wanted to be like that. Government organizations usually are very bureaucratic so you can’t do much as one person. I thought the best option was to start my own company.”

About the same time, he happened to read online about a Dutch company called Groasis that had invented a technology they claimed to be able to grow trees with very little water. Sarhan was intrigued but very skeptical. Planting forests in the arid Middle East could transform the landscape—and the health—of the region, but was it possible in climates such as Bahrain’s?

Sarhan worked with the Dutch inventor to adapt the technology for the Middle East and conducted his own trials in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait. The Groasis product is a planting container that feeds young plants, using stored water instead of continually irrigating them. After the first year, the container can be removed and the trees survive. Sarhan’s trials were a success, and his company has planted tens of thousands of trees in the Middle East over the past five years.

“These are desert trees, not fruit trees,” he says. “But they are still good for the environment, cleaning the air, providing shade for animals, and reducing dust storms. This can be transformative for the Middle East.”

Sarhan credits the fellowship for his success. “I learned scientific methods that I applied to adapting the technology at Emory, but more importantly, I gained the confidence and motivation to follow through,” he says. “If you don’t have examples of people who have really impacted their communities, you can’t imagine what it would look like. It’s not easy to leave a government job that pays well with set hours to go start your own business. The fellowship allowed me to imagine it.”

Fighting AIDS

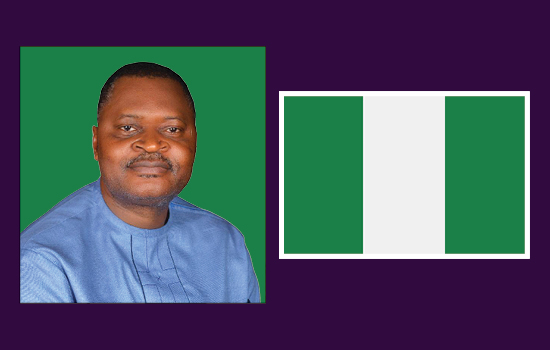

Godwin Etim Asuquo came to the Humphrey Fellowship in 2001-2002 specifically to learn how to deal with HIV in Nigeria. As the coordinator of primary health care training for nurses and midwives in the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria, he saw the devastation the disease was causing in his country.

“To date, the Humphrey Fellowship has been the most significant experience of my career,” says Asuquo, who also earned an MSN while he was at Emory. “By interacting with the professors, instructors, and other experts at Rollins, I gained much knowledge and skills around HIV prevention and treatment that I took back to Nigeria. I found that when I got back home, I was the expert on HIV.”

Asuquo used that expertise to develop national policies and training programs on HIV management and supported stakeholders at the national, state, and local levels to implement them. He worked with the federal government and then with USAID’s Policy Project to expand that work, with great effect. Asuquo’s work contributed to a drop in Nigeria’s HIV prevalence to 1.4 percent in 2019 from 5.8 percent in 2008.

Asuquo went on to serve as head of reproductive health and HIV/AIDS programs for the United Nations Population Fund and as chief party/program director for Save the Children USA’s Global Fund Program in Tanzania. Today he is back in Nigeria as executive director of the Africa Center for Health Leadership, a think tank on leadership issues in the health care delivery system. In this capacity, he is working to implement a program for universal health coverage and to establish a college of health, technology, and management.

“In Nigeria, health care institutions focus on how to deliver services,” he says. “Health care staff and providers lack leadership, management, negotiation, and partnership skills. We want to establish a college that emphasizes both health services delivery and leadership and management. We want to develop nurses, doctors, and community health workers who focus primarily on patient care, not on internal hierarchies.”

Humphrey Fellows who want to stay in touch with Rollins can contact Michelle James, senior director of alumni engagement, at michelle.james@emory.edu or Roger Rochat, Humphrey Fellowship coordinator, at rrochat@emory.edu