Epidemiology Epicenter

Rollins fellowship unites academic and local public health across Georgia

When Kathleen Toomey, MD, looks out over the state’s epidemiology workforce, she’s encouraged by what she sees. The situation, however, was quite different when the commissioner of the Georgia Public Health Department (GDPH) joined the office in 2019.

Kathleen Toomey, MD, commissioner of GDPH

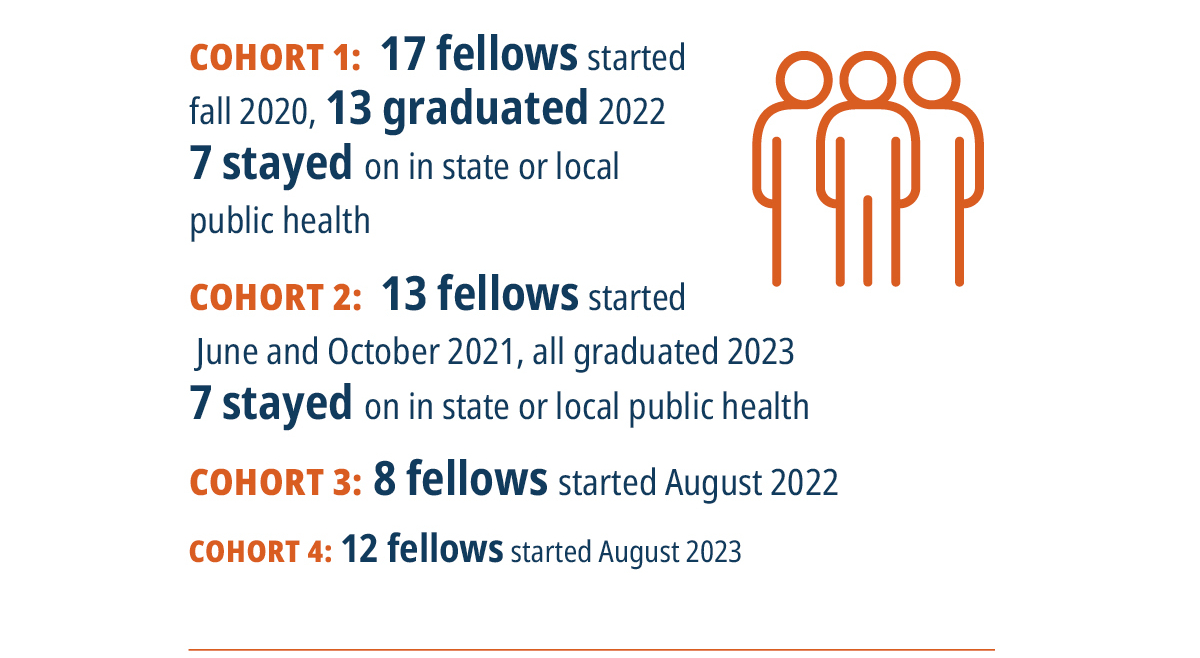

Today, epidemiologic capacity across the state is approaching robust levels thanks to the Rollins Epidemiology Fellowship. Now in its fourth cohort, the program was launched in the early days of the pandemic as a cornerstone of the Emory COVID-19 Response Collaborative, a partnership between Rollins and the GDPH. The intent was to bolster a meager epidemiology workforce in the 18 health districts across the state during a critical time.

The result, by any measure, has been a resounding success. Not only have the fellows provided invaluable personpower and expertise in helping local districts navigate the crisis, but they also continue to contribute as the pandemic wanes, allowing the districts to tackle local needs long relegated to the back burner. Perhaps most importantly, over half of the fellows to date have accepted post-fellowship jobs in state and local public health, the majority of them in Georgia.

“The fellowship has been successful beyond my wildest dreams,” says Toomey. “It certainly enabled us to respond much more effectively during the pandemic, but it did so much more. It allowed us to build a larger, more capable staff since many of the fellows have stayed on. It enabled us to engage faculty and focus meaningful research of value on public health practice. And it has raised the interest and enthusiasm of young, bright, future public health leaders. The fellowship has been a true game changer for us.”

Creation in a crisis

Declines in the public health workforce were alarming even before the pandemic. Between 2008 and 2019, employment in departments of health and public health across the U.S. fell by 16%, according to a report by the National Association of County and City Health Officials. A study published in a recent Health Affairs found that if separation trends continue, by 2025 as much as half of the governmental public health workforce will have left their positions.

Cherie Drenzek, DVM, state epidemiologist, GDPH

At the outset of the pandemic, each of Georgia’s health districts had at least one epidemiologist, but many of them had only one. It was clear this modest workforce would be drowned by the deluge of COVID-19 cases and their repercussions. “We were seeing numbers of cases reported for COVID alone that exceeded what we would normally see in a year for all diseases put together,” says Toomey. “The volume was beyond anything we could have imagined.”

Allison Chamberlain, PhD, research associate professor of epidemiology

Toomey had been thinking along the same lines. “Even before the pandemic, I thought there must be some way we can develop an academic, local public health partnership that would allow us to really strengthen our local capacity as well as give students an opportunity to see what local public health is like.”

Their vision became a reality thanks to generous funding by the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation. That support was subsequently supplemented by gifts from several local foundations.

The Rollins COVID-19 Epidemiology Fellows program (“COVID-19” was dropped from the name after the second cohort) was created as a two-year service and training fellowship. It was patterned, to a degree, after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS), but instead of recruiting terminal degree candidates (MDs and PhDs), it sought recent MPH graduates to be placed as entry-level epidemiologists within one of the state’s health districts or at the GDPH.

Fellowships kick off with an orientation week, providing each new cohort with an overview of the program and training, including strength-based leadership, public speaking, data presentation, and case interview techniques. Throughout their two-year stint, the fellows receive additional professional development and continuing education as well as regular sessions with faculty mentors.

The lion’s share of their time, however, is spent as frontline epidemiologists in their districts. For the health districts, the fellows have been a godsend. “There has been a lot of bad news nationally with respect to the state and local public health workforce,” says Chamberlain. “Our program is bucking the trend. The fellowship is really making a dent in the Georgia public heath workforce.”

Capacity for health districts

Seventeen fellows from the first cohort were placed with local health districts in the fall of 2020, and a second cohort of 13 fellows followed in the summer and fall of 2021. The timing could not have been better for Sandra Valenciano, MD, district health director at the DeKalb County Board of Health (DCBOH). She had just been promoted to her position from the post of medical director when three of the four epidemiologists in her office left.

Sandra Valenciano, MD, district health director, DCBOH

The original fellows—Sadaf Bhai 20PH in the first cohort and Zoe Schneider 21PH in the second cohort—hit the ground running, doing contact tracing, case investigations, developing staff protocols, updating documents, and messaging. “They were an essential part of our workforce almost from day one,” says Valenciano.

The experience was similar in the North Georgia Health District, which is headquartered in Dalton. “We were a very small department with just five people including one epidemiologist before the pandemic,” says Ashley Deverell, infectious disease director of the district. “So when the pandemic hit, we were just drowning.”

Bridget Walsh 21PH, member of the second fellowship cohort

Experiences like these were playing out all over the state. “The fellows provided not only boots on the ground to do the kind of work we needed to do very quickly and effectively, but they also came in with so much energy and enthusiasm,” says Toomey. “The staff in the districts and in the state office was just burned out, bordering on PTSD. These fellows were eager to learn and upbeat. They really helped create a positive team environment during a very difficult time.”

As the pandemic shifted from an acute to a chronic phase, the fellowship shifted as well, providing the manpower for districts to finally address projects they previously lacked the capacity to tackle. In DeKalb, Miranda Montoya 23PH, the district’s newest fellow, is leading a project to compile data and write a dashboard focusing on the health status of the county’s Hispanic/Latino population. Lucas O’Reilly, who received his MPH from Georgia State University and joined the district in the third cohort of fellows, has been preparing a health snapshot report for the county over a five-year period, writing a youth risk behavioral survey, and analyzing data around the county’s refugee clinic.

“We are unique in that we have a huge immigrant and refugee population in DeKalb County,” says Valenciano. “We have a clinic to serve that community, but no one had actually looked at the data involving the clinic. How many refugees have we seen? What are the most common diagnoses at the clinic? Lucas is looking at data collection tools and methods so we can do a descriptive analysis of the clinic.”

Andrew Lewis, member of the third fellowship cohort

In Dalton, Walsh worked on improving the district’s sexually transmitted infection (STI) services program, including placing posters with QR codes in schools and community gathering spots so people could discreetly scan the code and access information about sensitive, often taboo topics. The district is also looking into holding a health fair, an event it lacked the resources to pull off before the fellowship.

“Since the pandemic, the fellows have enabled us to get more involved in community projects and devote more time to prevention instead of just being reactionary,” says Deverell. “As every class of fellows has come through, we feel like we’ve been able to make strides in both areas.”

The fellows also brought freshly learned skills in data analysis and presentation. “The fellows have really improved our data reporting,” says Deverell. “We used to do most of our reports in Excel. Now we are getting into mapping, SAS (statistical analytics software), and other programs that allow us to create more visual, understandable reports to share with our stakeholders. It’s been a huge benefit to us.”

Today, Deverell’s office employs four epidemiologists, three of whom are current or former fellows.

Many of the fellows have submitted poster and oral presentations at local and national conferences—something normally outside the realm of local health districts. “From my perspective, that is the most unique part of the Rollins Epidemiology Fellowship,” says Drenzek. “It is the perfect marriage of the on-the-ground epidemiology that takes place every day in a local health department and the capacity, mentorship, and support of an academic partner like Rollins. That union allows that day-to-day epidemiology to be translated into science. Using what you learn on the ground to contribute to the body of scientific knowledge is what epidemiology is all about.”

Career boost for fellows

Like the EIS program after which it was patterned, the Rollins Epidemiology Fellowship offers participants a potentially significant boost along their career path. That word seems to have gotten out. For the last cohort of 12 fellows, the program received 172 applications.

Shelby Rentmeester 16PH, director of the Rollins Epidemiology Fellowship

Those opportunities were attractive to Walsh, who didn’t know the career path she wanted to pursue when she joined the North Georgia Health District. She originally thought she wanted to work at the CDC, which she did as an intern while earning her MPH. But when she joined the Dalton office, she felt like she had found her home.

“Working at the CDC was a really positive experience, but I felt removed from the communities I was serving,” says Walsh. “Here, I live and work in the community I serve, and I get to see firsthand the impact we are making. That’s really all you could want is to know that at the end of the day you’re helping someone.”

Though she had no previous experience in the area, Walsh early on transitioned from COVID-19 work to projects involving HIV and STI surveillance and prevention. Within just five months of joining the district as a fellow, Walsh became a full-time employee in charge of the district’s HIV and STI program. “It happened so fast, but the opportunity presented itself, so I took it,” she says. “I had never worked in HIV and STIs before, but I have found it to be some of my most meaningful work.”

Donovan Stephens, member of the first fellowship cohort

Stephens credits the opportunities afforded by the fellowship for his quick rise. When he started his stint in LaGrange, the district office, like those all over the state, was overwhelmed by the pandemic. With so few hands on deck, Stephens was quickly put in charge of COVID-19 outbreak response in long-term care facilities, schools, day cares, and jails. He performed so well that when monkeypox erupted in 2022, he took charge, sitting in on state meetings, developing training sessions for the district nursing staff and case investigators, and coordinating vaccination clinics.

With six months left in his fellowship, Stephens took advantage of the opportunity to enroll in the Region IV Public Health & Primary Care Leadership Institute, headed by Melissa (Moose) Alperin, EdD, 91PH, a mentor for the fellowship program. “It wasn’t just the invaluable information that was presented, it was also the connections you were able to make and the independent conversations you were able to have that made it such a special experience,” he says. “The institute and the fellowship really set me up for success.”

Stephens has now started a doctoral program in public health at the University of Georgia while he retains his position at the GDPH.

New and current fellows gathered for orientation sessions, training, and networking during the 2023 Fellows Retreat this past August.

Photography by Jack Kearse

The future of the fellowship

New and current fellows gathered for orientation sessions, training, and networking during the 2023 Fellows Retreat this past August.

Photography by Jack Kearse

The fellowship was created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Is it still needed and useful?

“Last summer, we did a comprehensive evaluation involving the state office and the local districts to determine if our program still has relevance in a post-COVID world,” says Rentmeester. “The answer from everyone was a resounding yes.”

Toomey corroborates that assessment. “I see the fellowship as even more important now,” she says. “Having this capacity allows the local health districts to get the same kind of picture of the community through an epidemiologic lens that we were able to get for COVID, and we never had been able to do that before in a consistent, effective way. I really see this program as the key to the future of our work as we move beyond COVID and address other issues.”

In fact, two new fellows who recently joined the GDPH will report not to communicable disease epidemiologists like they have in the past, but instead to the head of the department’s maternal and child health unit. They will focus on addressing health disparities around maternal mortality, including helping spearhead two new home visiting programs and other newly funded initiatives.

“Maternal mortality is a critical issue facing health departments across the country,” says Drenzek. “We haven’t had the capacity to truly tackle it before, but we decided to leverage our partnership with Rollins, which has vast expertise in this area, and use the fellows to develop epidemiologic capacity to study and respond to maternal mortality disparities.”

Additional fellows will be supported by a new grant from the CDC to establish a Center for Outbreak Analytics and Infectious Disease Modeling at Rollins. The center will be headed by Ben Lopman, PhD, professor of epidemiology and environmental health, and will fund six new fellows. These new fellows will form a bridge between cutting-edge epidemiology and public health practice.

“Academic public health and state and local public health are two different animals, with their own strengths and characteristics,” says Toomey. “This fellowship program brings the two together, and the result is a whole that is greater than either of its parts.”

THE ROLLINS EPIDEMIOLOGY FELLOWSHIP was made possible by generous support from the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation in addition to local foundations that supported fellows in their hometowns. Continued support is crucial to this vital program. For more information, contact Kathryn Graves at 404-727-3352 or kgraves@emory.edu

By the Numbers