Lessons in China Q&A

By Kay Torrance

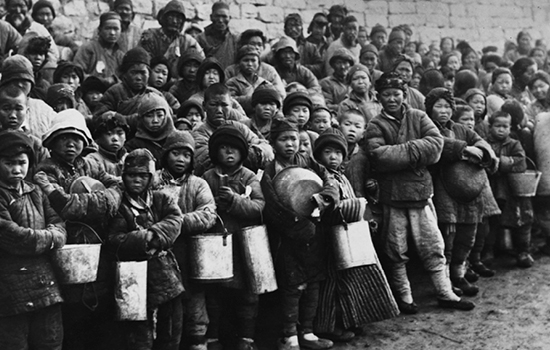

The Chinese famine of 1959–1961 may have been the worst in human history, killing an estimated 16 million to 40 million adults and children.

As a boy in Honduras, Reynaldo Martorell lived on a banana plantation, where his father earned a fair living. He often walked along the outskirts of the grounds, noting the difference between living conditions on the plantation and in the villages abutting it. The homes outside the plantation lacked running water and electricity. Malnutrition was chronic, and children were stunted. Though Martorell’s family was not rich, they were better off than people who lived in the villages.

Since then, he has devoted his life’s work to calling attention to the interplay between maternal and child nutrition. He was one of the first investigators to trace the long-term impact of improved childhood nutrition on health and development. In Guatemala, he studied a group of adults 40 years after they had participated in a nutrition trial as young children. Martorell connected their nutrition as infants to a range of outcomes as adults, including body size, cardiovascular disease risk, intellectual functioning, and wages. Better nutrition as children resulted in better outcomes as adults.

Today, Martorell is the Robert W. Woodruff Professor of International Nutrition and former chair of the Hubert Department of Global Health at Rollins. His honors include the Carlos Slim Award for lifetime achievement in research benefitting Latin American populations and election to the Institute of Medicine. He also serves as an adviser to UNICEF, the World Health Organization, and the World Bank.

|

|

Martorell continues to study the effects of childhood nutrition on adults in Guatemala in collaboration with global health professor Aryeh Stein and has undertaken projects in Mexico, Vietnam, India, and China. In the following Q&A, Martorell discusses his latest work to study the effects of the Great Chinese Famine on adults who experienced it as babies and young children during the late 1950s and the early 1960s.

Why study the Great Chinese Famine of 1959–1961?

The Chinese famine may have been the worst in human history, killing an estimated 16 million to 40 million people. It resulted from Mao Tse-tung’s "Great Leap Forward" campaign. He wanted to quickly industrialize China, so he forced people living in rural provinces into communes and put his attention and resources into massive industrialization. Soon there were sharp declines in crop production, and what little food that was produced was shipped to cities. There was little to eat for several years, and millions of people starved to death.

I have researched the long-term consequences of poor nutrition in early life, particularly in utero and the first two years (often called the first 1,000 days) for a long time. My early work showed that babies who were malnourished in utero and during their first two years of life were likely to be stunted and have lower IQs. So studying the effects of the famine was an extension of my interests. Starving is a horrible and senseless way to die, but I’ve often wondered about the millions of children who survived the famine. How are they faring today? So I began a series of studies with colleagues in China and with Cheng Huang, who was a postdoc at Emory. He’s now an economist with the Department of Global Health at George Washington University and developed the analytical model that we used in these studies.

What did you expect to find?

The first 1,000 days is a period of rapid organ development, including the brain. We expected to find that exposure to famine in early life would have a broad range of detrimental health effects in adulthood. And indeed we found that these now-adults have an increased risk of hypertension, overweight, and mental illness. Other researchers in China have reported effects related to schizophrenia and income.

Studying the Chinese famine is challenging because it was nationwide and didn’t have an abrupt beginning or an end. We relied on comparing cohorts exposed to the famine during pregnancy and after birth to cohorts born much earlier (exposed at later ages) or after the famine (unexposed). We looked at data sets from large studies or surveys that included adults born before, during, and after the famine.

Did your findings surprise you?

Yes. In one study we found that babies born to women exposed to the famine in early life gave birth to bigger babies compared with unexposed women. This is puzzling because we demonstrated in the same data set that such exposure led to women being shorter as adults; therefore one would expect smaller babies. We think this counter-intuitive finding is due to survival selection. Fertility was sharply reduced during the famine, and fetal and neonatal mortality significantly increased. Women conceived during the famine and exposed to it as infants must be a very select sample and may represent a "hardy" group with a greater potential for growth, which was dampened by the famine but expressed in the next generation.

Are you doing any follow-up to these studies?

Cheng and I recently completed two studies, one that shows that early life exposure to the famine led to a greater risk of low IQ and speech disabilities and another that shows famine exposure was linked to greater risk of an increased concentration of protein in urine, suggesting impaired kidney function. We also want to do two more studies—one on famine and cardiovascular disease risk in adults and another on a variety of health and economic outcomes.

How would you like the results of these studies to be used?

Our findings point to the importance of good nutrition in early life for future health and well-being. We hope that China and other societies across the world will take this to heart and invest in women and children. For example, Chinese women are still affected by iron-deficiency anemia and other micronutrient deficiencies, especially zinc. Improving programs to distribute these supplements should be a top item on China’s public health to-do list.

|

||||