KO For TB

Emory researchers have long studied tuberculosis, and with good reason. Though there are drugs to kill it and a vaccine to prevent the worst forms of it, TB remains one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases, killing more people each year than HIV/AIDS, influenza, or malaria.

However, Emory’s TB scientists have been scattered across different schools and departments and had few options for collaborating and cross-pollinating with colleagues in other parts of the university. “It’s almost like having a piece of a puzzle: you’re looking at it, but you’re not seeing the big picture,” says Dr. Kenneth Castro, professor of global health.

So Castro, along with Dr. Neel Gandhi, professor of epidemiology, and Dr. Jyothi Rengarajan, infectious disease associate professor in the School of Medicine, decided to bring all those disparate puzzle pieces together, forming the Emory Tuberculosis Center. Launched in March 2020, the center connects experts from Rollins, the School of Medicine, Yerkes, the DeKalb County Board of Health, and others. This diversity of membership allows the center to serve as a crossroads for biomedical, epidemiological, clinical, translational, and public health research. At every step of the way, investment and research need to be rapidly translated to practice, a process facilitated by the eagle’s eye view of the whole puzzle offered by the center. “The intervention is worthless until you apply it to the people who need it,” says Castro.

And people desperately need it. “Even though we have now been able to cure TB for more than 50 years, and we know how to prevent it, people still are dying of it,” says Gandhi.

Ebb and flow of TB

Each year, some 10 million people fall ill with TB and about 1.5 million people die from it. Up to a quarter of the global population is infected with TB, although only 5 percent to 15 percent will experience active disease.

In the mid-twentieth century, the world made rapid advances against TB, progress that was fueled by improved nutrition, sanitary conditions, and medical care. Today, about 85 percent of people who develop TB disease can be successfully treated with a six-month drug regimen. That success has led many in high-resource countries to consider TB a disease of the past.

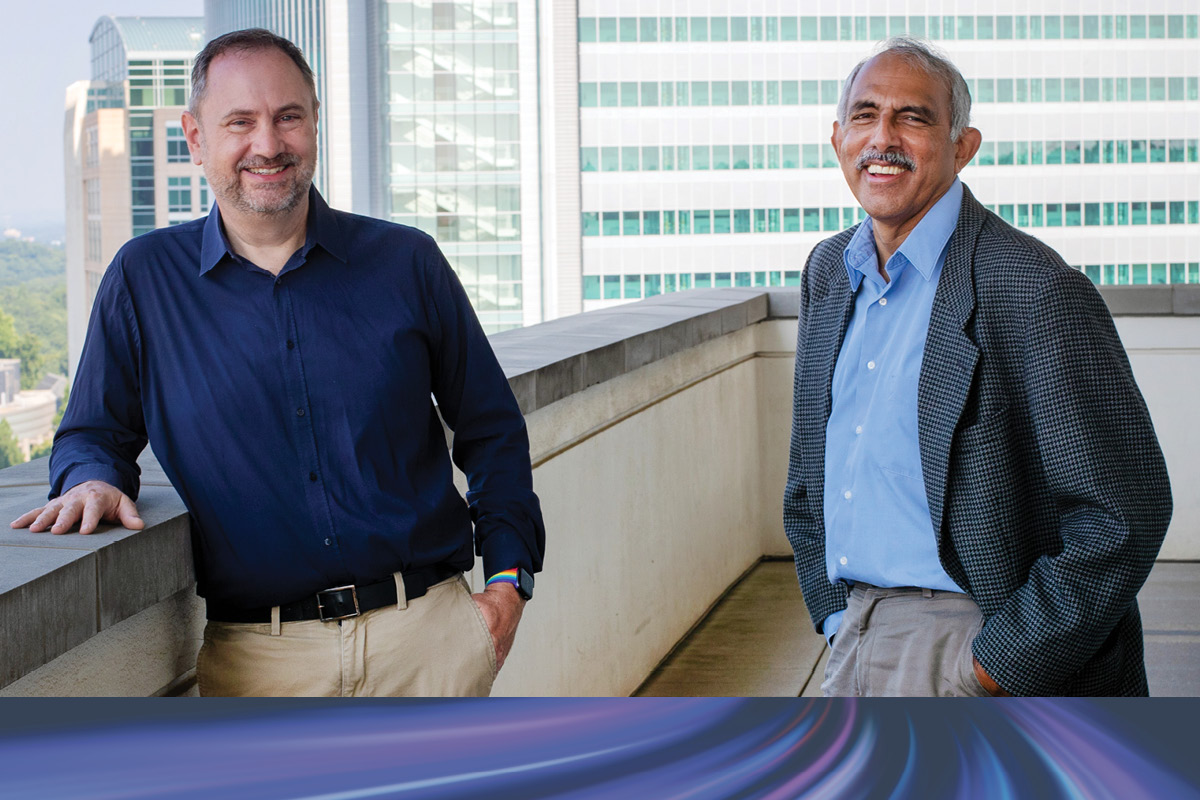

In low-resource countries, however, TB is very much a disease of the present. Many living in poverty simply can’t access the life-saving treatment. In fact, 30 countries account for almost 90 percent of TB illnesses each year. Jyothi Rengarajan, Kenneth Castro, and Neel Gandhi (l-r) lead the new Emory Tuberculosis Center.

Even in high-resource countries, the disease is regaining a foothold through strains that are drug resistant, causing infections that are nearly impossible to treat with current methods. After 30 years of enjoying an annual 5 percent decrease in TB cases, the US became the first country to experience a resurgence of TB, fueled both by the emergence of multidrug-resistant TB and the rising frequency of TB/HIV co-infection.

“It really shows what happens when you prematurely declare victory over a disease such as tuberculosis,” says Castro, pointing to the sense of complacency that preceded the resurgence.

Although the US has since regained much of that lost progress, infection rates have remained high among certain populations, including people who are foreign-born, homeless, or incarcerated. Many immigrants acquire latent TB infection in their home countries; the active, contagious form of the disease and its characteristic bloody cough might not manifest until years after arrival in the US. Castro highlights the importance of global cooperation, emphasizing that, “a disease that has no borders should not have preventive control measures that stop at our borders.”

Gandhi adds,“TB doesn’t discriminate.” After all, it’s caused by a bacterium—Mycobacterium tuberculosis—that’s transmitted through the air. Its spread is facilitated by social and environmental conditions that are often outside of people’s control. Although most common in low-income settings in countries such as India and China, the disease still has a foothold in the US. Georgia has one of the highest rates of TB in the country. Only a few years ago, Atlanta experienced an outbreak of drug-resistant TB stemming from a large homeless shelter.

Bringing researchers together

The center serves as a hub for TB education, training, and research. It offers extensive curriculum options for pre- and postdoctoral researchers to learn new methods and techniques. It co-hosts workshops, guest lectures, and a monthly “Work in Progress” meeting for local researchers and students. Over the past 10 years, Emory TB Center faculty members have provided mentorship and research training for 351 US and 91 international trainees. This includes more than 40 Rollins public health students, including eight doctoral students in epidemiology.

The center will also provide continuing education and refresher courses for practicing physicians and other health professionals. After all, TB is so rare in the US that most physicians have never seen a case. Castro himself has seen the impacts of physician education, recalling a returned Peace Corps volunteer whose extensively drug-resistant TB diagnosis might have been missed if not for a colleague involved in research at Emory. Neel Gandhi accompanied a community team door-to-door in Indore, India, to diagnose individuals with TB.

Some of the center’s research has been sidelined by the COVID-19 pandemic, with researchers pivoting to address the more pressing need. At present, the effect of the pandemic on tuberculosis incidence is unclear. Many infectious respiratory diseases have plummeted in the wake of social distancing and increased hygiene measures, and the world saw larger-than-expected decreases in TB in 2020. In the US alone, disease fell by 20 percent.

These numbers likely are muddied, however, by the attention focused on the pandemic. Many health care facilities, overwhelmed by COVID-19 cases, might not have had the time or resources to diagnose or record new TB infections. Castro also suspects that an overlap might exist between deaths attributed to COVID-19 and TB, which both weaken the lungs of patients.

Despite the distraction, the center is nurturing several projects on the molecular, physiological, and social consequences of TB. One recent study from Emory researchers, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, used blood markers to distinguish between active and latent infection. Another examined how a drug called bedaquiline might improve outcomes of patients with rifampin-resistant TB. Other studies analyzed the pulmonary impairment among patients with HIV/TB coinfection, the benefits of preventive therapy, and the long-term mortality of patients who didn’t finish treatment.

As a graduate student at Emory, Dr. Kristin Nelson studied the spread of TB in sub-Saharan Africa and had the opportunity to visit a hospital for patients with drug-resistant TB in South Africa. “It is devastating to see the impact of this disease up close,” says Nelson, assistant professor of epidemiology. “Now, I am interested in how we can prevent TB altogether.” To do that, she leads research on the implementation of new TB vaccines. Kenneth Castro testified before Congress when he was rear admiral of the US Public Health Service Commissioned Corps.

Dr. Sarita Shah, associate professor of epidemiology, focuses on TB prevention from another angle: transmission. An expert in HIV/TB coinfection and drug-resistant TB, she recently published a study on the transmission of drug-resistant TB in South Africa. Like Nelson, she’s also spent time in foreign hospitals and marvels at the resilience of the staff there.

Here in Georgia, Associate Professor of Epidemiology Dr. Matthew Magee recently published a study on the prevalence of latent TB among diabetic patients at an Atlanta hospital. He says, “There are so many unanswered questions about TB in public health, and the solutions are extra challenging due to the intricacies of the infection. TB research is stimulating because it requires creativity and developing impactful solutions spans so many disciplines.”

“We need to keep moving the edge of the envelope and not be satisfied,” says Castro. “In the trajectory of medical and health research, you have a series of building blocks, and you keep building on the past achievements. Every now and then you’re lucky enough to leapfrog over those and you have a big Eureka moment.”

They’re hoping for some Eurekas.